by Mary-Terese Cozzola

We could have saved sixpence. We have saved fivepence. (Pause) But at what cost?

—Samuel Beckett, All That Fall

What happens when you lay your playwriting out on the bed, hanger upon hanger, sweater upon mismatched sock of complete play drafts, half-written monologs, title ideas, snatches of dialog? What happens if you hold and thank each item, let go of the ones that don’t bring you joy, and store the rest in a way that truly serves you going forward?

To tidy a home, Marie Kondo works a category at a time: clothing, books, etc. So if you’re up for this adventure, start by identifying the big categories that make up your playwriting. For me, it’s Digital and Paper.

Day 1. Digital.

Step 1. Lay out your digital writing on the bed.

To do this, I opened my local drive and my Dropbox folder to display as much of my writing as I could on my big iMac screen. What a mess—a motley assortment inconsistently named files, some placed in folders, others not. When I’m actually looking for a file, I usually search on a text string because browsing through all these windows succeeds only in making me feel like a loser for having so many versions of so many files.

A challenging thing about digital writing is that often there isn’t one final, unchangeable version of a piece. Even if a play has been produced, you might continue to tinker with it, thereby creating new versions of the file. And even if you have a “perfect” draft, what about all the previous ones? Part of me wants to delete them, so that I have just one file per play or story. If some scene or line got cut along the way, I probably don’t need it, right?

But then I remember my first playwriting teacher, the late Fred Gaines, saying that at a certain point you should go back to the first draft of a piece, to reengage with your original idea, before you “perfected” it. That’s one of the most useful pieces of writing advice I’ve ever heard. As you change and grow as a writer, you might come back to an early draft and see it differently, a process that could take you in a different, more exciting direction.

Then again, you don’t need to keep every single version. Sometimes that feels too heavy. Argh, how to decide? Luckily, we have a plan that supports making the keep-or-toss decision quickly and decisively.

Step 2. Create a beautiful storage cabinet.

This is one main folder that will hold your biggest category of playwriting. I’ve created a folder called Writing. I created it in my main Dropbox folder so it’s accessible from everywhere. I also created separate main folders for Teaching and Plays from Others, because those are important aspects of playwriting, but I don’t want to confuse them with my writing, which deserves its own beautiful cabinet.

We’ll build shelves for this cabinet in a minute. First, we need to make it easy to toss what we don’t want.

Step 3. Create a Compost bin.

This is a folder named zzzCompost (the zzz keeps it at the bottom of the folder list). This is where you toss files that don’t bring you joy, but it’s better than your computer’s trash bin.

In a month or a year, you can open zzzCompost and pull something that sparks your interest (watch out for worms), or you can make permanent deletions. For now, it allows you to remove files and folders with abandon. One of the perks of digital writing is that it doesn’t take up much space, so you can afford a nice big zzzCompost bin.

Step 4. Create another bin for ideas you haven’t written yet.

I called this zzUnassigned so it sits just above the Compost bin. This is for ideas and web links and anything else that’s interesting but hasn’t found a home yet. I like the name Unassigned because it makes those ideas feel important. They are wanted and valuable, they just haven’t been given a mission yet.

Step 5. Create a limited number of shelves in your cabinet.

Each shelf is a subfolder for one type of creative writing. I experimented a lot here. First I tried detailed subfolders like 10-Minute Plays, Full-length Plays, Stories for Performing, Stories for Reading. But this gave me too many shelves. So I ended up with something much simpler: one folder for each medium, like Plays, plus my two bins.

Step 6. Hold each document...

In your mind’s eye. Thank and release the ones that don’t bring you joy. Remember you’re just moving them to the zzzCompost folder, so this doesn’t need to take forever.

Step 7. For each piece you keep, create a folder on a shelf, and place all drafts of that piece in it.

From all 57 drafts of your novel to one draft of a one-minute play, each piece gets a folder. Otherwise, files get crumpled in dark corners instead of standing up in neat vertical folds. A folder also gives you a great place to put notes, research, and anything else related to the writing of this piece.

If you’re not already using a consistent file-naming system, now is a great time to start. I’ve started naming my files Title_of_piece.dd.mm.yy—for example, Bolshoi Bathtub.091619. If the piece is a related document, reflect that as well—eg, Bolshoi Bathtub.cut scenes.091619. I’m not going back and renaming everything, but going forward this makes the contents of each folder easier to survey.

If you come across a file that’s not truly part of your playwriting process, like a lecture on dialog or a quote you love, plop it into a separate main folder and deal with it later. Maybe set a different date for Marie Kondo-ing your teaching.

Day 2. Paper.

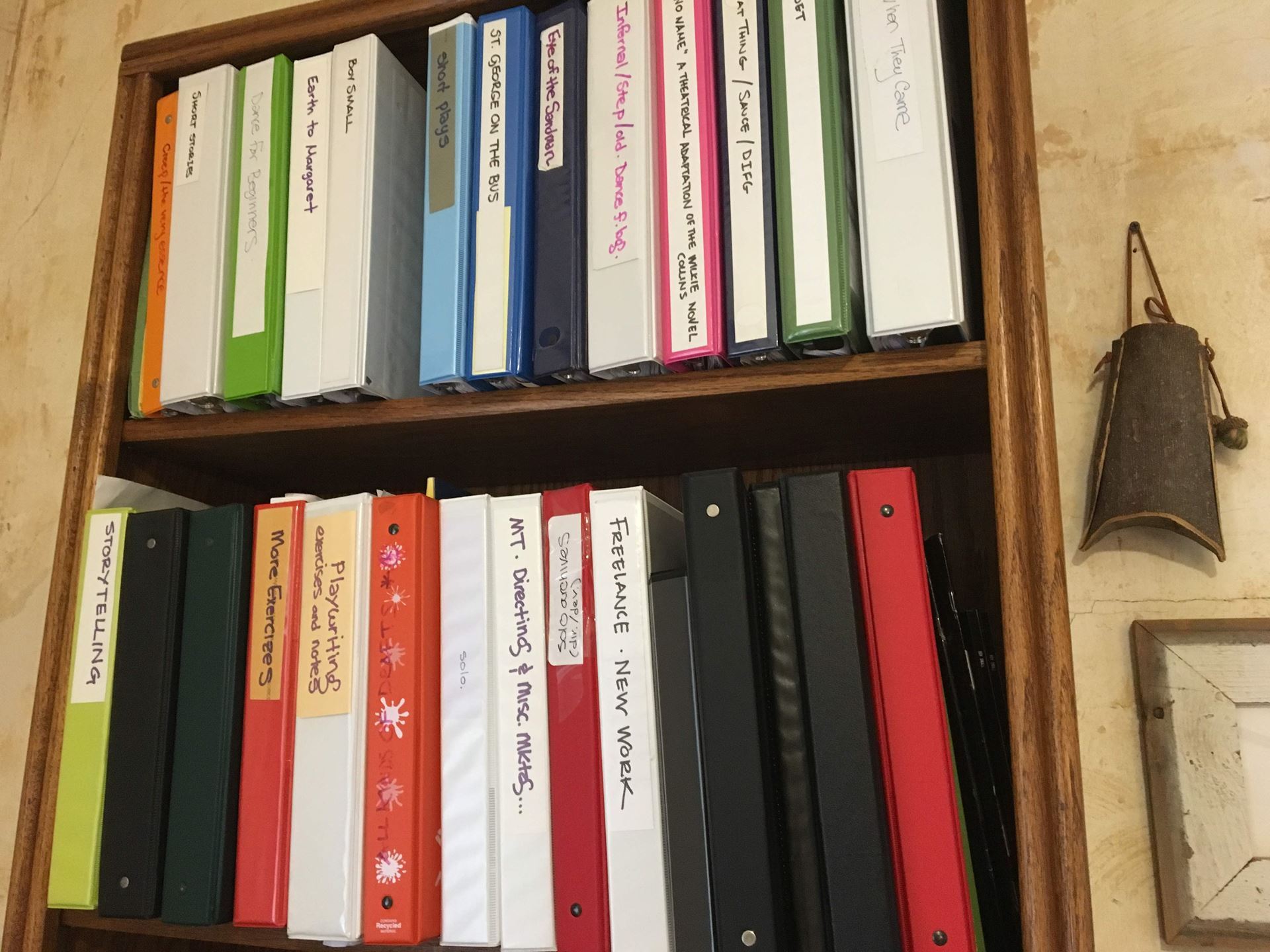

Once you tidy your digital writing, it’s time to move to the physical stuff. For me that’s an overwhelming number of binders, loose papers, dozens of diaries, countless blank books friends have given me “to write in” that are too pretty to actually write in, loose notes, playbills, newspaper clippings, and more. Most of it is crammed into a grim oak bookcase in my office, jammed into a filing cabinet, and stacked at the back of my desk.

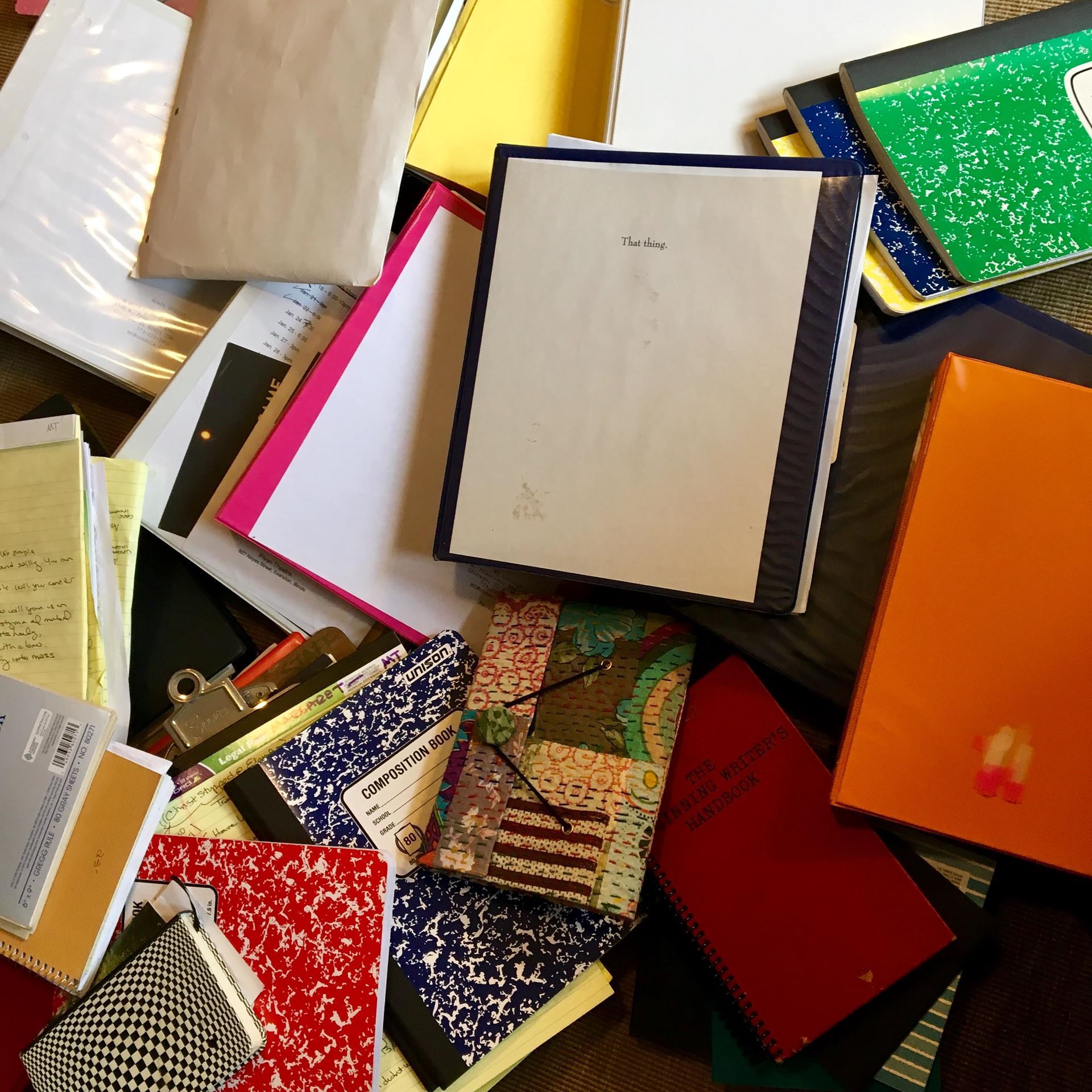

Step 1. Pile everything on the bed.

Or, in my case, on the floor. At first, I resisted this step, because a few years ago I created a binder for every full-length play I wrote, every class I taught, and every category of shorter writing. Old drafts, notes, contact sheets, programs, feedback, everything was filed into these binders. I spent countless hours making tabs for different kinds of writing exercises. I bought document sleeves to put programs and cast notes in. I labelled each binder on the spine.

I was really proud of these binders. I didn’t want them on my floor. I wanted to cheat this step and extract one item at a time because my floor is not that big and I need it for yoga. But as soon as I dropped the first notebook, I realized two things:

-

Binders have no touch appeal. In their plastic-i-ness and random colors and Sharpied spine labels, they don’t shout, “creative synergy!” but instead mutter, “windowless computer lab.”

-

I almost never use them. When I need something, 99% of the time I pull up the most recent digital draft instead.

But I’d put so much work into hole-punching and Sharpie-ing. Was it all for nothing? And what about all the journals and notes that have no digital equivalent?

Step 2. Sit down with an expert.

For advice, I turned to writer and producer Jill Howe, who has been posting beautiful photos on Facebook of her tidying process all year. Over corncakes, Jill confided, “Before, with storytelling I did everything on paper. And I would keep every draft, so I’d have like 20 drafts of a story. I mean, it was kind of fun in the beginning, like, ‘Look at all the work I’m doing!’ But if you’ve told a story now and then you tell it again in two months, you look back and go, ‘I ended the story like that? What the eff was I thinking?’ So now, when I do a piece for a show, I have the final draft, and that’s really the only paper I keep. I don’t need the 20 drafts that got me to that point.”

Jill admitted that there’s the stuff that’s easy to toss, the stuff that’s easy to keep—and then there’s everything in between. Luckily, she also had a solution for this, the largest category in most of our lives.

Step 3. Get some apps. Or not.

Jill uses the notes-app-on-steroids Evernote and Evernote’s free Scannable app to digitize and organize all the in-between stuff. “The app takes a picture, immediately crops it to the frame, and turns it into a high-quality image,” she explained. “You can make folders in your Evernote for all the different categories, and scan directly to those.”

If you already use Dropbox, like I do, it includes a built-in scanning feature that I’d never noticed until Jill showed it to me. Just click that plus sign icon on the phone app and start scanning.

Jill also has a WiFi scanner that she keeps on her desk, along with a tray for day-to-day stuff like bills and receipts. “When the pile gets deep, I pull out the scanner,” she said. She recommends the Doxie, which runs about $200, handles multi-page documents pretty well and promises to sync easily with all major cloud services including Evernote and Dropbox.

Step 4. Hold each document…

Once you’re set up with a scanner or two, you’re ready to:

- Pick up a notebook or stapled pile of something.

- Turn each page.

- Decide whether to keep the whole thing, toss the whole thing, scan selected pages, or scan all the pages.

- Put the binder in a donation bin.

- Thank and then trash every page you can possibly live without.

- Trash sacred words? Like, in an undignified recycle bin?

Step 5. Have a bonfire.

About that whole written-words-are-sacred thing I was feeling? Jill’s been there, too. “I’ve been carrying around journals since I was in college,” she told me, “you know, repressive, horrible poetry. And you know, that whole corny thing about, does it spark joy? It just reminded me of things I didn’t want to remember. So I asked a friend, ‘hey, can we build a fire in your backyard?’”

So instead of tossing my outgrown scribblings in the recycle bin, I’m collecting them for a bonfire, first day it’s warm enough to sit outside around the fire pit and toast some marshmallows.

Step 6. Stay motivated.

Jill advises taking before and after pictures to remind you of why you’re doing this, and to help fine-tune your work. “There’s something about taking pictures,” she said. “I would declutter a space, take a picture of it, and—I couldn’t see this in real life, but when I’d look at the picture I’d say, ‘that’s still too much.’ And I’d go back and get rid of more.”

Warning that if you do pile everything on the floor, you may kick yourself or curse this post. Going through everything will probably take longer than you planned and the mess may haunt you. But that’s exactly why the pile is brilliant. You’ll be extra-motivated to move quickly so you can get what you want: a beautiful, uncluttered space to write in, and a digitized library of documents, journal entries, and notes you can access from anywhere without ever having to dust.

MT’s plays have been produced by Piven Theatre, The Side Project, Chicago Dramatists, The Fine Print Theatre, Working Women's History Project, and elsewhere. She has received awards from the Illinois Arts Council and Heartland Theatre, and residencies at The Ragdale Foundation, Playa, and Hawthornden Castle. MT has taught playwriting and story development at Carthage College, The Second City Training Center, and in private workshops. Her dramatic writing has been published by Applause Books, Hippocampus Magazine, Crawdad Literary Journal, and Original Works. She lives in Chicago, and is represented by the Robert A. Freedman Dramatic Agency. https://mtcozzola.com/

![]() at the top of the post

at the top of the post![]() at the top of the post

at the top of the post