by Amy Oestreicher

A World Becomes a World…

Auschwitz. A camp I heard so much about. In books and stories in history. But what I crave was more than history. I wanted to know what it must’ve been like for my grandmother, as she survived, but all that followed, and how she pieced her life back together after such life shattering trauma.

It was my Uncle Morris, whom the rest of my family told me was more passionate about playing bridge than telling stories, that finally came to my rescue.

I interviewed my uncle for nearly a year, and for someone whom I hadn’t even met yet, we developed an indescribable closeness through our vulnerable exchanges on life, love and loss.

“We never thought of the fact of whether we would see them again or would not see them again, I just don’t think we thought that way, you know, every day was a survival day, and we lived for that day. Thank God we all joined up after the war.

It’s funny that you mention it, that I never thought to ask Hannah what it was like to be liberated from the camps. I’ve often felt that pain from all of this – the war years, that she went through as – the worst possible thing that a woman could go through.”

Through my relatives, I found a way in. I found that just by asking, their words opened up new worlds not only for me, but for them.

“Besides her lemon bars which my mouth waters every time I think of them, I remember that she always loved me and made me feel important. It was your grandma that gave me the confidence that I have always had. That’s what I enjoy remembering about her. I will continue tomorrow because right now my tears blind me. Love you, Morris.”

The Family Detective

I learned how to be strategic with my oral history interview questions. We only remember something that we have recorded or encoded at the time we experienced it. Something may trigger or jog our recollection. One vivid memory might take us back to a whole series of events. A photograph can trigger a memory, response, or arousal. Once the event is recalled, it is ordered and shaped by the narrator. Memories are not just stored, they are newly constructed, combining information to support the immediate situation.

I started a weekly dialogue with Morris and could never have anticipated what I’d learn.

Uncle Morris:

“I can’t even imagine how life would be different without the war, and all of those millions who perished and were tortured.

It’s always been a puzzlement to me, for my survival, because I was such a sick child, knowing that many of my friends did not survive after the war, or my oldest brother. Unfortunately, everyone is gone right now, except myself.

My view of heaven is being together with family from the past who have passed away, and still getting the care and love that I felt from each one of them. when I look at an old picture of my family, I just remember especially how… special they made me feel. They were so wonderful to me, and I don’t know if I ever told them and I am sorry I didn’t, how special they were all to me.

What would Grandma be like today?

She would have been so very proud and happy to see you Amy, that you have survived your own ordeal, as she had survived hers, and so proud of what you went through now, connecting, organizing and getting all of this information about her, and her family.

I hope all of this comes together eventually, and perhaps, wishful thinking, I’m hoping that you and my son can write a book together when this is all finished. I will try to gather whatever photos I have and make copies, and whatever I can send you, I will send you directly to your house, myself.

I guess the only time I really think of Hannah now is when I look at the pictures in the house and I see her. And it’s the same as the rest of the family – my dad, my brothers – but I guess that is why you have pictures, so you can remind yourself once in a while, of the past.

I don’t know who said this, but I think I remember someone saying that as long as we carry our loved ones in our heart they are never truly gone. You and I and the rest of us, when you were, cannot possibly imagine the excruciating pain and suffering she has – she was forced to endure in concentration camp – oh yes we have all even pictured it and know her stories, so we think we know, but we don’t.

I know you personally have survived your own very tragic and painful time in your life, and I am sure you continue with this pain to this day. But you have grown to be a survivor and heroically tell your story to all who will listen so they can also learn about human suffering. It is important for them to know. Especially people who are fortunate enough not to have walked through those gates, but even the ones need to know that they are never alone.

(clears throat)

Cherish your gifts and talents to spread the news. It is how civilization survives. We all learn from it.

I personally do not agree with those who say, “As they come in, they come out.” How would that be possible? Some people are born very poor and get very rich, and vice versa. Life is constantly changing and giving you opportunities.

For example, my own life story is…. difficult for me to believe. From a small town in Europe, we came to the greatest country in the world, and have been blessed with many brothers, sisters, aunts, uncles, children, grandchildren and great grandchildren and cousins and…. many others who are now in all fields of human endeavors, touching so many lives as they go along the way. What we learn most from your grandma is to carry on and do the right thing, and to set a good example for others to follow. I think that is the best way to honor their legacy.

Anyway, I will try to continue later on. Thank you.”

“Re-Viewing” Family

These words opened up worlds. They opened up my heart. They opened up a family to possibilities that no one knew existed.

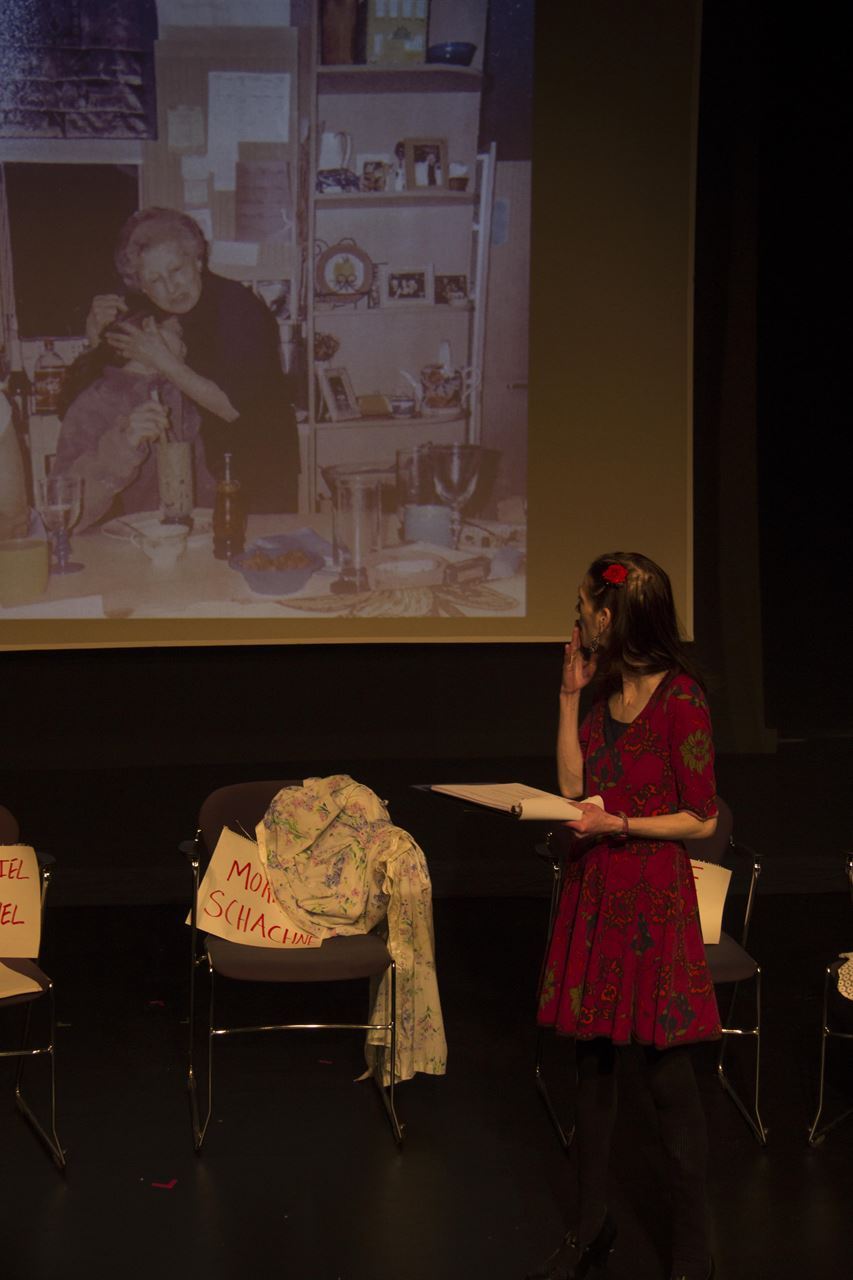

I put together hundreds of these transcribed words and created a solo performance piece, “FIBERS” in honor of my Grandma, whose skillful sewing saved her life in the concentration camps.

When I performed FIBERS in public for the first time, not only was I giving voice to Uncle Morris, the story of my Grandmother, and her eight siblings, all but two who had passed on. I was giving voice to an entire era that is threatened every day to fade from history if we don’t keep asking questions.

Stories can not only give a voice to the powerless in society, but can help the individuals find their own power and move forward in their lives. In telling the story, for example, of my great uncle Morris, his family members told me he had never been happier, and was opening up for the first time. I was allowing my family members to tell their stories, and allowing them to move on after such a horrific past in surviving the Holocaust.

I have high hopes for my docudrama, FIBERS. For 90 minutes, I’m embodying 12 family members’ accounts of what they could remember. But what makes for more fascinating material, is what they couldn’t remember. Writing this play was about putting these puzzle pieces together and allowing a powerful story to be fully realized in the process.

A Detective Becomes the Family Playwright

Those that argue that oral history is not “reliable” are countered by those who believe the experiences of ordinary people, and their anecdotes are truer than written document. In order to write FIBERS, my job as a playwright was to facilitate remembering. I became fascinated with the stories that the subjects create to hold the memories together – not just the memories themselves. Without memory, there are only cold, hard facts. Theatre is about heart. So is life, and so is the family I came to know in the process.

FIBERS was inspired by the literal sewing my grandmother was forced to do in the concentration camps in order to stay alive. And by telling stories, asking questions, and not giving up our innate capacity to stay curious, we reconnect the fibers of our past, our legacy, who we are now, and the future we can create.

I’ve always known theatre has been about collaboration. But this was the greatest collaboration of my entire career.

Of course, I’m only 30.

But as I learned from interviewing my great-great-uncle Isi in Belgium, keeper of the family’s genealogy…we’ve been around for centuries.

Now THAT’S a long-term collaboration!

Amy Oestreicher is a PTSD peer-to-peer specialist, artist, author, writer for Huffington Post, speaker for TEDx and RAINN, health advocate, survivor, award-winning actress, and playwright, sharing the lessons learned from trauma through her writing, mixed media art, performance and inspirational speaking.

AirPlay Presents: Amy Oestreicher's Fibers: https://podtail.com/en/podcast/airplay-1/airplay-presents-amy-oestreicher-s-fibers/

![]() at the top of the post

at the top of the post![]() at the top of the post

at the top of the post