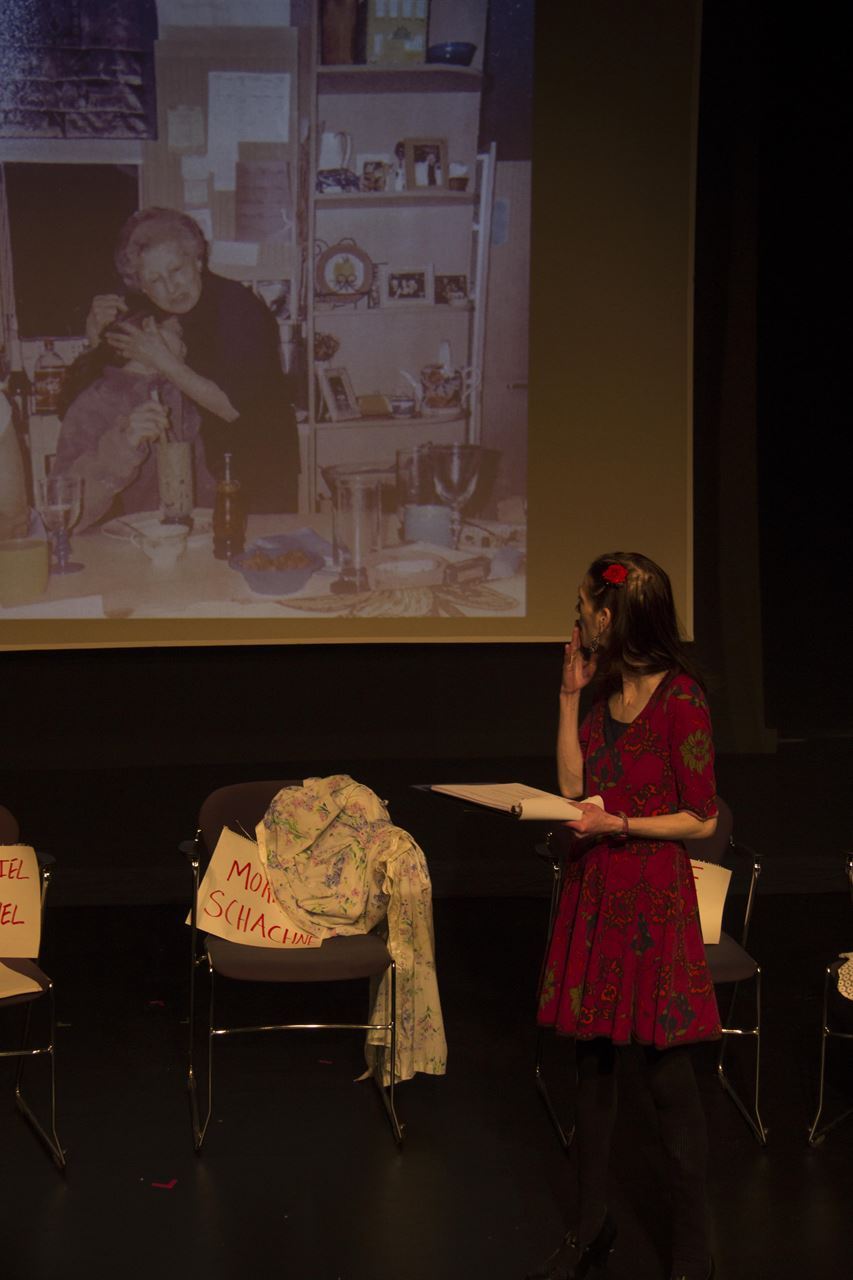

Questioning meaning, Holocaust legacies, and "questions" through Theatre, Part 1.

by

Amy Oestreicher

“How could you not remember when you found out Grandma was a Holocaust survivor?”

Marilyn: I don’t remember.

Amy: Well…[getting frustrated] okay. But like –

Amy: Well when did you know what the Holocaust was?

Marilyn: I might have blocked it out. Who knows. Ask my brother.

Amy: I’m wondering why you don’t remember –

Marilyn: I just always knew it. No, I probably – probably heard it when I was younger and just didn’t understand it.

Amy: Well…having always known it – how did that make you feel then?

Marilyn: What do you mean? I just accepted it.

Amy: But it’s not a fact like your eyes are blue – it’s –

Oy. That’s how it all started.

I wanted to know my more about my grandmother who had passed away while I was in a coma at 18 years old. I had always looked to her spirit for strength, through my own dark times.

I decided I wanted to ask other relatives – people I only had seen in old wedding albums and on Facebook feeds.

At first, I was discouraged to delve into my family history. Why didn’t anyone think this was worth the pursuit?

I called my uncle. His response?

“You’re not gonna get anything – unfortunately I reached out to all of the relatives, everybody, and I’m telling you and nobody knew any of the story – just so you know, when I was going to write my book, after a while I realized there was so little information, like accurate information, that it was gonna have to be a fiction based on historical events. None of this is non-fiction. It’s very frustrating.”

The more relatives I asked in my family, the more I resonated with my uncle’s frustration.

My grandmother, a Jew in Czechoslovakia during World War Two, had been married just 5 weeks when she was taken by the Nazis to Auschwitz, separated from her 8 siblings and saw her husband shot and killed. She survived the war. She made it to Brooklyn, NY, on a ship that marked the rest of her life with an overwhelming fear of the ocean, married a tailor, and together, they established a successful sewing corporation in the garment district. She, and others like her, never really got to talk about all they had seen, and having endured more pain and felt more fear in those few years than most people in a lifetime, their generation raised children while trying to keep so much bottled up inside. She did her best to keep this fear and pain from her daughter, my mother, and while my mother remembers her as the most loving, sweetest mother, she also remembers feeling a real sadness and fear in her home.

Was that why my mother had “blocked it out?”

When “Nothing” Becomes Everything

According to my mother, my grandmother never spoke much about anything.

“She never talked about the atrocities. She would talk about bread, pieces of bread, people stole from people, she said there were all kinds of people in the camp – good, bad, generous, they lived off potato peels. She said that when they first got there, they had to go in lines, and Dr. Mengele – the crazy “doctor” who did all of those experiments – he told them which line to go on. And Grandma always said that one nurse talked to Mengele, and while she was talking to Mengele, Grandma pulled her friend to the other line, and that is what saved their lives. Grandma also had an abortion. After I was born – she felt like she was too sick to have another baby, and she went to a terrible abortionist in someone’s living room – who almost killed her with a hanger – you know, that’s how they killed them in those days, and she felt guilty forever – you know, a lot of guilt about a lot of stuff…”

One question was leading me to traumas I didn’t even know I should be asking about. Was I ready for that?

The Power of Asking

I realized that one, unassuming question (combined with a bit of gentle prodding and persistency) could open up a stream of remembrances and possibly unjam Lethe’s river of forgetfulness. Perhaps every “I don’t remember” and “They didn’t tell us anything” was simply a deceptive curtain. I read books on history and memory, the generation of postmemory, dug through oral history archives and Jewish history databases, and I searched through oral history archives, called museums, libraries, and old diners in Brooklyn where I knew my grandparents had frequently dined. I went on to create twelve comprehensive oral history guides for family members I hadn’t even met. I was determined to follow the trail of (or lack thereof) memory, too see where it may lead.

One relative connected me to another, and soon, I was getting emails and Facebook Messages from people I didn’t even know I was related to. I introduced my quest with one question:

“Do you remember my Grandma?”

Mostly, the answer was, “A bit. She was sweet. Quiet. Great cook.” But the more questions I asked, the more discoveries I made… including the passionate longing my grandmother always felt for her first husband.

What? A first husband? Before my Grandpa?

One relative recalled, “That’s what she seem to have trouble talking about, just that she loved him a lot . But not much else… like, you knew that the Holocaust had taken a toll. You’d ask her about what it was like, in the old country, and she would make little asides and not even know it? Maybe nothing specific, but you could just tell there was something.”

Between the “I can’t remembers” and “I don’t knows,” the more I asked, the more people seemed to remember about my Grandma’s first husband – the mystery man with no name, photo, or documentation. Another relative revealed, “When they separated the two of them, they were hiding in a tobacco farm. She and her sister were playing outside. Nazis came, and they grabbed her and beat her. Her older brother ran out of the house, and said “Don’t touch my sisters, take me.” First they put him in a jail, and Grandma and Aunt Betty would sneak to the jail, where they saw him tied up in chains, and grandma always felt guilty. Her brother went to the camps and died there, but everyone else in the family survived. Everyone got separated, they were separated for months – it was a miracle they all met back in America. Sad – Hannah [my Grandma] always thought she would die and her husband would live because she always said, he was so strong. Same with her brother.”

Wait, Grandma’s brother died?

“You’ll Never Find Enough Facts”

Every “answer” led to more unresolved questions, which opened more gaps in what I thought I knew. Soon, I was prompted to ask about events, places and people I never had heard about in my entire childhood from a family I thought I knew inside out.

An aunt then warned me as I dared to tread further, “It was kind of an unstated rule when you’re with Holocaust survivors that you don’t go there. and nobody comes out and says it, but it’s true for all of us that are first generation – you just grew up knowing you didn’t go there.”

But I went there.

I went “there,” just to end up in a maze, in search of facts, dates, and places with no “finish line” in sight. Throughout this tireless pursuit, my relatives were sure to constantly remind me that I’d never find enough facts.

“It’s like the telephone game. The story changes the more people you talk to.”

“All you’ll get is memory. No history.”

Re-Thinking Success

But in the end, what was I looking for that was really important to me? History or memory?

What I discovered was an even greater gift than history. I found precious family anecdotes that even my own mother didn’t know. I discovered that every family member had a personal piece of history and in stringing them together, I was creating the family narrative.

I interviewed nieces, nephews, great aunts, uncles, grandparents, distant cousins, and far distant cousins from Belgium, France, Prague, Israel, and San Francisco. I went to research and history archives and uncovered photographs and old documents from my past, including the ship that my grandparents came to America on. I logged hours transcribing tape upon tape and discovered that a word can become a whole world.

Humans claim to love facts, but I think we truly, in our hearts, treasure stories and memories more. What I uncovered were greater truths than I ever could have found in a history book. These words of my family members – many of these words just telling me “I don’t know anything,” opened up an entire world for me.

Part 2 to be published soon...

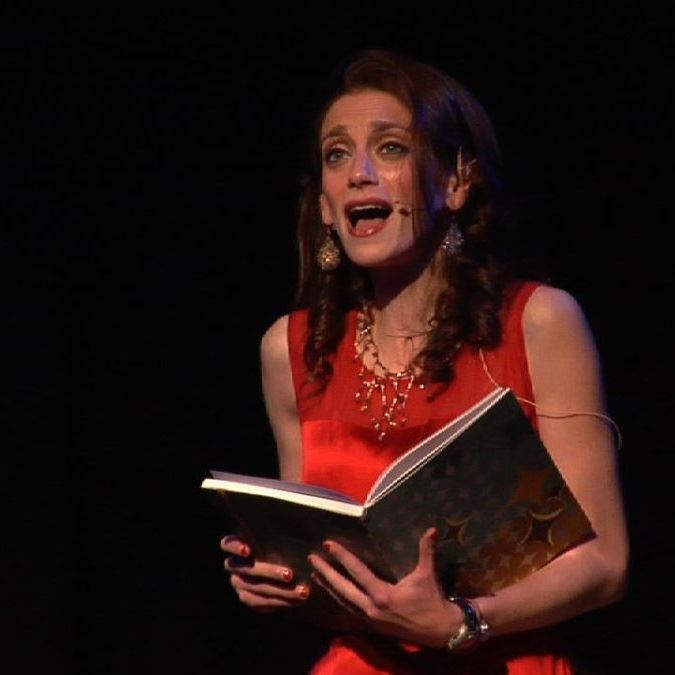

Amy Oestreicher is a PTSD peer-to-peer specialist, artist, author, writer for Huffington Post, speaker for TEDx and RAINN, health advocate, survivor, award-winning actress, and playwright, sharing the lessons learned from trauma through her writing, mixed media art, performance and inspirational speaking. As the creator of "Gutless & Grateful," her BroadwayWorld-nominated one-woman autobiographical musical, she's toured theatres nationwide, along with a program combining mental health advocacy, sexual assault awareness and Broadway Theatre for college campuses and international conferences.

https://www.amyoes.com

https://www.amyoes.com

![]() at the top of the post

at the top of the post![]() at the top of the post

at the top of the post